Syria Conundrum

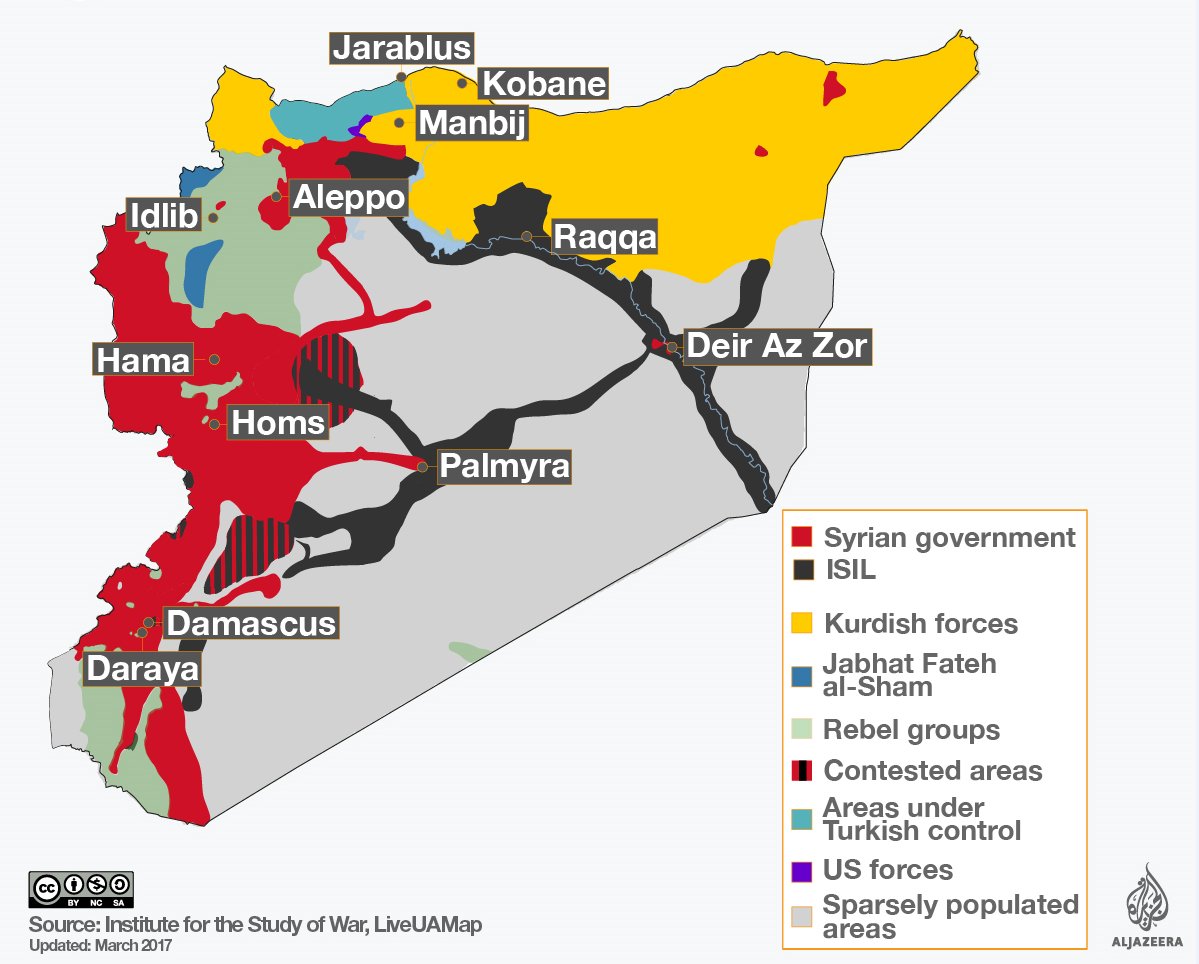

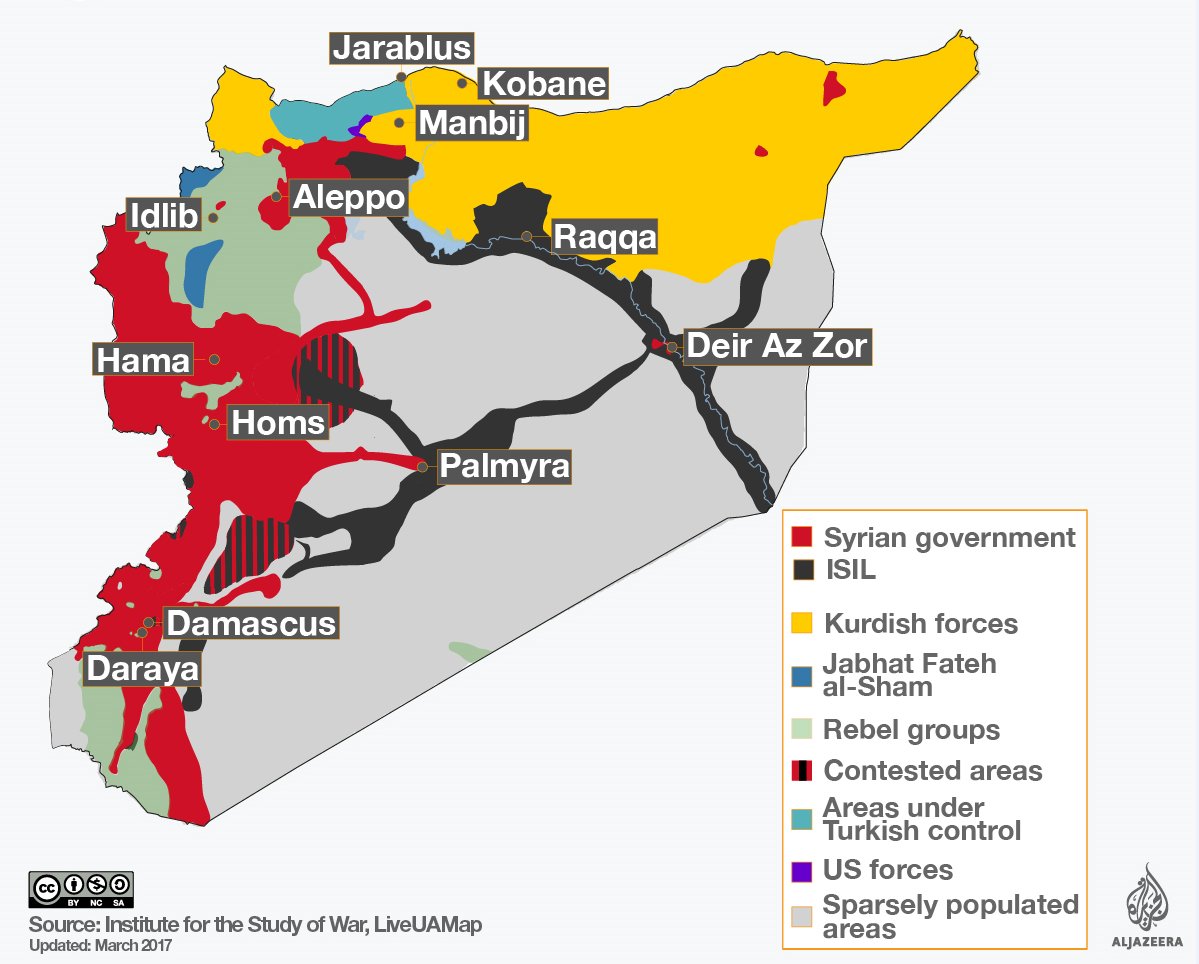

"Red lines" have been crossed and an embolden new administration itches to flex America's military muscle. Russian and Iranian actors continue to support a detestable Assad regime, allowing the Syrian leader to deploy chemical weapons against his adversaries. Over a six year time period, Syria is a messy and complicated quagmire befuddling "foreign policy experts" and the political leadership within both the Democrat and Republican parties, as seen in the current military/political reality on the ground.

Since March 2011, when initial protests against the Assad regime began, American's attention to Syria has waxed and waned. Particularly, specific situations have influenced American public opinion on what our reaction should be. The chemical attacks in 2013 (on Ghouta area of Damascus) and the recent attack on Khan Sheikhoun in Idlib province, have invigorated the debate on a military response in Syria. Yet, the refugee crisis and anti-immigration sentiment in the U.S. has driven an isolationist narrative.

For years we hear this conflicting sentiment: either the U.S. is too involved in world affairs as a detriment and fomenting anti-Western sympathies; or the U.S. is the indispensable country and not doing enough to elevate humanitarian crisis. It is ironic to have both narratives playing at the same time.

This dual narrative of the U.S. in a "damned if you do, damned if you don't" situation is the backdrop of any pending intervention.

Most professional pundits advocate one of two possible situations. Either it is: all in with a robust military intervention and capturing and securing territory; or this civil war is not in vital American interests. Both positions are wrong and right.

Let's be honest, the events in Syria are not a direct threat to U.S. national security or interests. Syria does not have the capacity to export military capabilities against U.S. interests outside of the region. The conflict has provided an environment for terrorist organizations to thrive but their reach extends to the immediate vicinity and with limited capability, Europe.

U.S. military intervention is an option but there should be an exit strategy and overall strategy on what should be in place after the military re-deploys. Unfortunately, the way U.S. political leaders, and some military leaders think, an exit strategy is not a priority. This plays into a foreign policy mindset which is reactionary instead of setting a strategy and moving towards stated long term goals.

Finally, the responsibility to end the humanitarian disaster caused by the Syrian war belongs to the world community. If there was ever a reason for the existence of the United Nations the Syrian civil war is that reason. According to the UN Charter Chapter I, a purpose of the UN is to: "To maintain international peace and security, and to that end: to take effective collective measures for the prevention and removal of threats to the peace, and for the suppression of acts of aggression or other breaches of the peace, and to bring about by peaceful means, and in conformity with the principles of justice and international law, adjustment or settlement of international disputes or situations which might lead to a breach of the peace..." The UN has failed and the collective world community has failed the Syrian people. Individual political interests need to be set aside to facilitate an end to this civil war. And everyone needs to understand they will not give everything they want.

What is the U.S. role in Syria?

The U.S. military has a spotty record intervening in humanitarian crisis. Just go back to the 90s and look at the bungled U.S. intervention in Somalia. The debacle ended with a significant U.S. foreign policy bloody nose and a retrenchment of U.S. military power resulting in non-intervention in Rwanda and later limited intervention in the Balkans with sides that reached a point of exhaustion. Time and time again we see U.S. military intervention to alleviate humanitarian crisis as half-assed measures which the U.S. government wants to do on the cheap. An U.S. military presence in Syria requires a well understood mission with well defined end-states, an exit strategy, and what is the U.S. government's role after the military intervention.

The U.S. military cannot be the main military force driving an end to this civil war. Additional American militarism in the region is a recruitment tool and rallying cry for Islamist extremists and back home the American public will not support another large scale American military adventure in the Middle East. But we cannot sit by and watch as innocents are gassed or driven to flee in rickety boats to find safety in an increasingly intolerant European mainland.

Instead, the U.S. role needs to be more nuanced. We should be facilitating a more robust response through the UN and the Arab League to end the civil war and subsequent humanitarian crisis.Instead of a large "boots on the ground" presence, an American approach should emphasize logistical support for an UN and/or Arab League led international coalition; deployment of robust intelligence gathering capability - mostly Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance; Signal Intelligence; Imagery Intelligence; Geospatial Intelligence - and a mandate for intelligence and information sharing; a robust air campaign to establish safe havens for displaced personnel along with aggressive rules of engagement and free fire target zones for unmanned aerial vehicles; and advisors to train, assist, and advise local state and non-state partners. I would be bold to suggest that advisors are also embedded with Iranian units to de-conflict battle space issues. Quick digression: the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, unless it finds some alternative form of economic ascendency, will become less of a geopolitical player as its oil/gas reserves are depleted and the world moves away from fossil fuels while Iran has a history of being a significant actor in the Middle East and with an opening society may be able to regain clout in the region as it grows economically.

If the U.S.' strategic objective is to foster an end to hostilities and pursue an inclusive Middle East policy, then the military cannot be the primary answer but instead a more robust and bold diplomatic and development arms need to be at the forefront. As noted in one of my earlier posts, the U.S. needs to look at diplomacy in a new light. The old paradigm of stuffy and regal diplomats, bunkered behind their high-walled palaces, is passe and a relic of an earlier time.

New and emerging threats are not like we have not seen before. The delineation between friend and foe is razor thin so the U.S. diplomatic community needs to shift mindsets. U.S. diplomats, especially the ambassadors and embassy staffs, need to be more engaged with local populace and even with more of the nefarious characters in some of these conflict zones instead of being in their air conditioned protected embassies.

How does this robust diplomatic presence translate in Syria? A new breed diplomat should be embedded with some of the same non-state partners (Kurds, anti-Assad rebel groups such as National Coalition for Syrian Revolutionary and Opposition Forces and the Free Syrian Army, al-Quds forces, Druze militia groups, etc.) along with a military advisor. These diplomats are the President's representative, relaying U.S. policy positions and facilitating more inclusive U.S. assistance, both during and after the civil war. Having one of these enhanced diplomats with non-state actors provides a mechanism for the U.S. to understand and address their needs during and after the conflict. Also, that person will be able to advocate for pertinent non-state actors to be a part of any negotiated settlement.

An enhanced diplomat can bring the third element of the D3 triad into play. Living, breathing, and working with non-state actors, the diplomat can provide realistic expectations on development project that will help the affected people and to win hearts and minds. They should intimately know the needs of the actors and can assist in advocating for long term development projects for the effected communities.

We cannot follow the common U.S. intervention. Syria is broken and the world community needs to take responsibility in assisting the Syrians, to include all minority communities, resolve this conflict. As the major world geopolitical power, the U.S. cannot shirk its responsibilities and entrench ourselves in an isolationist policy. We must lead diplomatically, developmentally, and support militarily. But it will come down to the actors in this horrific play to self-determine their own status and as a nation we need to be able to quickly assist when possible. We cannot let neo-colonialism impulses dictate our involvement.

Since March 2011, when initial protests against the Assad regime began, American's attention to Syria has waxed and waned. Particularly, specific situations have influenced American public opinion on what our reaction should be. The chemical attacks in 2013 (on Ghouta area of Damascus) and the recent attack on Khan Sheikhoun in Idlib province, have invigorated the debate on a military response in Syria. Yet, the refugee crisis and anti-immigration sentiment in the U.S. has driven an isolationist narrative.

For years we hear this conflicting sentiment: either the U.S. is too involved in world affairs as a detriment and fomenting anti-Western sympathies; or the U.S. is the indispensable country and not doing enough to elevate humanitarian crisis. It is ironic to have both narratives playing at the same time.

This dual narrative of the U.S. in a "damned if you do, damned if you don't" situation is the backdrop of any pending intervention.

Most professional pundits advocate one of two possible situations. Either it is: all in with a robust military intervention and capturing and securing territory; or this civil war is not in vital American interests. Both positions are wrong and right.

Let's be honest, the events in Syria are not a direct threat to U.S. national security or interests. Syria does not have the capacity to export military capabilities against U.S. interests outside of the region. The conflict has provided an environment for terrorist organizations to thrive but their reach extends to the immediate vicinity and with limited capability, Europe.

I contend there are significant regional and geopolitical implications. The Middle East is at a breaking point, with sectarian interests in direct competition and increased violence. How the Syrian civil war plays out may portend to a larger regional disintegration. Sectarian relations seem to be at the lowest point in decades and is exasperated by proxies pulling the strings of the various actors. A breakdown of the current Middle Eastern Westphalian nations is definite possibility.

U.S. military intervention is an option but there should be an exit strategy and overall strategy on what should be in place after the military re-deploys. Unfortunately, the way U.S. political leaders, and some military leaders think, an exit strategy is not a priority. This plays into a foreign policy mindset which is reactionary instead of setting a strategy and moving towards stated long term goals.

Finally, the responsibility to end the humanitarian disaster caused by the Syrian war belongs to the world community. If there was ever a reason for the existence of the United Nations the Syrian civil war is that reason. According to the UN Charter Chapter I, a purpose of the UN is to: "To maintain international peace and security, and to that end: to take effective collective measures for the prevention and removal of threats to the peace, and for the suppression of acts of aggression or other breaches of the peace, and to bring about by peaceful means, and in conformity with the principles of justice and international law, adjustment or settlement of international disputes or situations which might lead to a breach of the peace..." The UN has failed and the collective world community has failed the Syrian people. Individual political interests need to be set aside to facilitate an end to this civil war. And everyone needs to understand they will not give everything they want.

What is the U.S. role in Syria?

The U.S. military has a spotty record intervening in humanitarian crisis. Just go back to the 90s and look at the bungled U.S. intervention in Somalia. The debacle ended with a significant U.S. foreign policy bloody nose and a retrenchment of U.S. military power resulting in non-intervention in Rwanda and later limited intervention in the Balkans with sides that reached a point of exhaustion. Time and time again we see U.S. military intervention to alleviate humanitarian crisis as half-assed measures which the U.S. government wants to do on the cheap. An U.S. military presence in Syria requires a well understood mission with well defined end-states, an exit strategy, and what is the U.S. government's role after the military intervention.

The U.S. military cannot be the main military force driving an end to this civil war. Additional American militarism in the region is a recruitment tool and rallying cry for Islamist extremists and back home the American public will not support another large scale American military adventure in the Middle East. But we cannot sit by and watch as innocents are gassed or driven to flee in rickety boats to find safety in an increasingly intolerant European mainland.

Instead, the U.S. role needs to be more nuanced. We should be facilitating a more robust response through the UN and the Arab League to end the civil war and subsequent humanitarian crisis.Instead of a large "boots on the ground" presence, an American approach should emphasize logistical support for an UN and/or Arab League led international coalition; deployment of robust intelligence gathering capability - mostly Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance; Signal Intelligence; Imagery Intelligence; Geospatial Intelligence - and a mandate for intelligence and information sharing; a robust air campaign to establish safe havens for displaced personnel along with aggressive rules of engagement and free fire target zones for unmanned aerial vehicles; and advisors to train, assist, and advise local state and non-state partners. I would be bold to suggest that advisors are also embedded with Iranian units to de-conflict battle space issues. Quick digression: the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, unless it finds some alternative form of economic ascendency, will become less of a geopolitical player as its oil/gas reserves are depleted and the world moves away from fossil fuels while Iran has a history of being a significant actor in the Middle East and with an opening society may be able to regain clout in the region as it grows economically.

If the U.S.' strategic objective is to foster an end to hostilities and pursue an inclusive Middle East policy, then the military cannot be the primary answer but instead a more robust and bold diplomatic and development arms need to be at the forefront. As noted in one of my earlier posts, the U.S. needs to look at diplomacy in a new light. The old paradigm of stuffy and regal diplomats, bunkered behind their high-walled palaces, is passe and a relic of an earlier time.

New and emerging threats are not like we have not seen before. The delineation between friend and foe is razor thin so the U.S. diplomatic community needs to shift mindsets. U.S. diplomats, especially the ambassadors and embassy staffs, need to be more engaged with local populace and even with more of the nefarious characters in some of these conflict zones instead of being in their air conditioned protected embassies.

How does this robust diplomatic presence translate in Syria? A new breed diplomat should be embedded with some of the same non-state partners (Kurds, anti-Assad rebel groups such as National Coalition for Syrian Revolutionary and Opposition Forces and the Free Syrian Army, al-Quds forces, Druze militia groups, etc.) along with a military advisor. These diplomats are the President's representative, relaying U.S. policy positions and facilitating more inclusive U.S. assistance, both during and after the civil war. Having one of these enhanced diplomats with non-state actors provides a mechanism for the U.S. to understand and address their needs during and after the conflict. Also, that person will be able to advocate for pertinent non-state actors to be a part of any negotiated settlement.

An enhanced diplomat can bring the third element of the D3 triad into play. Living, breathing, and working with non-state actors, the diplomat can provide realistic expectations on development project that will help the affected people and to win hearts and minds. They should intimately know the needs of the actors and can assist in advocating for long term development projects for the effected communities.

We cannot follow the common U.S. intervention. Syria is broken and the world community needs to take responsibility in assisting the Syrians, to include all minority communities, resolve this conflict. As the major world geopolitical power, the U.S. cannot shirk its responsibilities and entrench ourselves in an isolationist policy. We must lead diplomatically, developmentally, and support militarily. But it will come down to the actors in this horrific play to self-determine their own status and as a nation we need to be able to quickly assist when possible. We cannot let neo-colonialism impulses dictate our involvement.

Comments

Post a Comment